What does it take for a golfer to make a successful comeback from injury, trauma or just a horrendous slump? MICHAEL VLISMAS explores for Compleat Golfer.

Gary Player leaned forward and clasped his hands together. ‘Let’s be honest,’ he said, ‘it’s a mountain for him to climb now. And not just any mountain. It’s more like Everest.’

It was November 2017, during the Nedbank Golf Challenge at Sun City. In a quiet room at the Gary Player Country Club clubhouse, Player was discussing what faced Tiger Woods as he prepared to make his comeback to tournament golf.

‘There is always a limit to something,’ the great man said.The pertinent question in professional golf and, indeed, all sport, is when is that limit reached?

And it becomes an even more pertinent question when dealing with the comeback. Successful returns in sport are difficult enough, but in professional golf they seem even more rare. Perhaps it explains why golf has its own literature for comebacks, which it narrows down to even a player’s ability to claw their way back from a six-shot deficit and win, never mind emerging from a lengthy slump or even an absence from the game.

It’s also for this reason that golf is still celebrating Jack Nicklaus’ 1986 Masters triumph. He was 46 years old and, in the opinion of many, a spent force. He hadn’t won a Major in six years. The media had written him off before the 1986 Masters. He took great pride in staring at a column from the Atlanta Journal stuck to the fridge of his accommodation at that Masters by a friend, which declared what everybody was thinking.

‘According to that piece I was finished, washed up, kaput; the clubs were rusted out; the Bear was off hibernating somewhere; it was all over and done with, forget it, hang ’em up and go design golf courses or whatever,’ Nicklaus said.

To be fair, he described his victory as coming in ‘the December of my career’.

‘I’m not as good as I was 10 or 15 years ago,’ he told the gathering of golf writers after his victory. ‘I don’t play as much competitive golf.’

He hadn’t been sidelined from the game by injury or any personal issues, as was the case with Woods, but make no mistake, this was still as close to a comeback as Nicklaus would ever come.

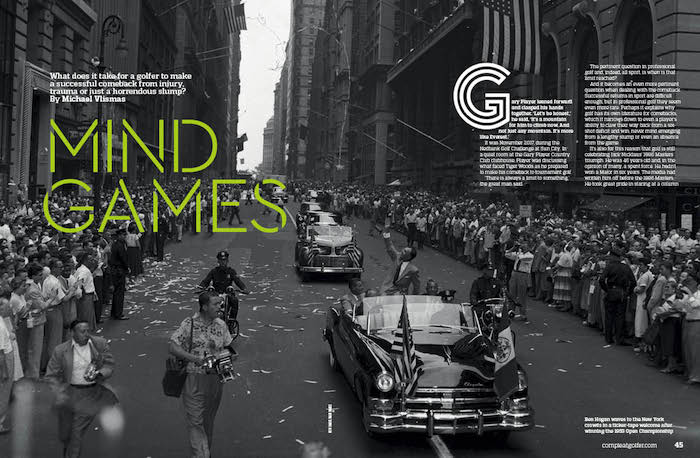

Ben Hogan made one of the most remarkable comebacks in all sport when he returned from a head-on collision with a bus in 1949 and won the 1950 US Open.

Doctors said he would never walk again. Golf writer James Dodson notes in his official biography of Hogan how, on a cruise ship after the accident, Hogan was talking with two other writers and explaining to them how he still believed he could win tournaments. Noting that he was still a ‘cripple’, both writers shook their heads when Hogan left, with one uttering, ‘How pathetic.’ He won the US Open 11 months later. In fact, he won a further five Majors, which means Hogan won the majority of his total of nine Majors after having his body mangled and nearly dying in that car accident. Perhaps the greatest comeback in the history of golf.

Ken Venturi also suffered a car accident, struggled with recurring injuries and even alcoholism, but came back from that to win the 1964 US Open.

But for every story of Nicklaus or Hogan, there are countless others of failed comebacks.

What, then, is the anatomy of a comeback? What determines who has what it takes to make a comeback, and who is simply going to fade away, as predicted?

‘There are two things that are important in performance: one is your focus and two is that you have a good foundation,’ says Dr Jannie Botha, a leading sports psychologist who works with professional golfers, as well as the Bulls and the Springbok Sevens teams.

When considering someone like Woods, Botha says, ‘In the world of performance both of these – foundation and focus – were stripped from him. Getting them back is really hard work.’

Botha adds a third factor that comes into play, and which professional athletes such as golfers have a particularly hard time dealing with: real life, and the effect either injury, tragedy or personal failure has on them.

‘It’s a case of dealing with the reality of life happening to you. When a professional golfer is “in the bubble”, like most other professional sportsmen, he does not have to deal with that side of life. Now, suddenly, it’s raw and in his face most of the time. How he is going to react to that will affect his performance.’

It can be argued that a golfer such as Hogan was so supremely talented that this alone enabled him to make the successful comeback he did.

Woods clearly fits this mould, too. But Botha doesn’t agree that natural talent alone guarantees a successful comeback in golf.

‘Having that natural talent might be a blessing and a curse, because these players are so naturally talented they are above the rest up to a certain point. Then the rest pass them and they struggle to understand why. The problem is that natural talent will only take you to a certain level. To compete with the others from that level is hard work. When that golfer makes a decision to work hard, they become successful.’

Player echoes this belief as he considers what Woods, in his prime, shared with his own values.

‘Striving for perfection. Hard work. Highly focused. Determination. Failure was never an option. It never entered my mind. But interestingly enough, as you get older, you can see failure possibly happening because you are weaker. Your mind, your body. Nothing lasts forever.

‘I don’t think Tiger could have gotten better. And having made some wrong decisions and the injuries, it may have taken away his great ability.’

Having worked in several areas of professional sport and with a variety of elite athletes, Botha is convinced professional golf has a unique set of pressures and challenges that make it one of the hardest sports in which to make a comeback.

‘I don’t think there is another sport in the world as close to real life as golf. It’s almost the principle of the harder you try, the less it happens, and the more you release the more it comes your way. It is not fair; the bounce of the ball may save you shots or may cost you shots. You cannot stop in the middle, you have to finish.

‘When you accept this you are almost able to handle and enjoy golf more; it is the same with life. Once you have accepted this trauma in your life – say, five balls in the water for a 13 – you are able to carry on and make birdie. In the sense of a comeback, when you work through your setback or trauma, it will definitely make you a stronger person mentally.

‘Mental toughness has five areas of development, and trauma would definitely affect the foundation of mental toughness. Once it’s channelled correctly, the outcome is positive.’

Interestingly, though, Player identifies ‘striving for perfection’ as one of the greatest strengths of his career. But not a perfection-driven attitude.

A failing body and the inevitable toll of millions of swings can bring a professional golfer making a comeback to a point where he is frustrated by remembering the shots he used to hit and is no longer able to.

But Player says he was never focused on hitting a perfect shot at all costs.

‘No, because golf is such an intricate game and there is a limitation. In other walks of life, there may not be. But when the ball is in the air, anything can happen. You have to accept that sometimes a perfect shot ends in sheer disaster.’

So, in the anatomy of a comeback, is there a particular route to take to ensure success?

‘If I was the one advising a golfer making a comeback, I would like him to understand that your natural talent got you to where you are. But you need more to get to the next level,’ says Botha.

‘Then I will definitely create a foundation which he understands and feels safe with, in his subconscious. I’d teach him to focus correctly, and he will be successful again. That would be my starting point.’

The same starting point that is the first step – to climbing Everest.

– This article first appeared in the May issue of Compleat Golfer